In the past few years, many Hong Kong people have immigrated overseas. I believe that every reader has more or less familiar relatives and friends who have decided to leave their hometown. They leave for different reasons, but they also need to adapt to a strange environment. Even though we no longer live in the same city, those who remain here still care about the local lives of overseas Hong Kong residents. After the housing problem is gradually solved and the living environment becomes familiar, finding sources of income becomes an urgent issue. Many immigrants have heard that the job market in foreign countries is not as active as in Hong Kong. However, they may not be prepared for it. They may be willing to sacrifice how much hard work they have done in the past and work in a sub-optimal job just to "earn a living".

Immigrant groups lack social capital and career downgrades are common. How serious is this phenomenon among overseas Hong Kong residents? After changing jobs and careers, will they be able to get satisfaction from their jobs? How to express the pressure caused by immigration?

Students from the Department of Global Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong conducted research on Hong Kong immigrants in the UK under the guidance of the author. Online questionnaires were distributed from July to December 2023. With the assistance of non-political diaspora organizations living in the UK, they published in monthly electronic publications and on-site events Display the image code of the online questionnaire and received responses from 1,237 Hong Kong residents who immigrated to the UK. The content of the questionnaire focuses on many aspects such as population, work, life and media consumption of Hong Kong immigrants to the UK. Today, we share with readers the real-life work situations of the interviewees before and after immigration.

Revenue declines, with few exceptions

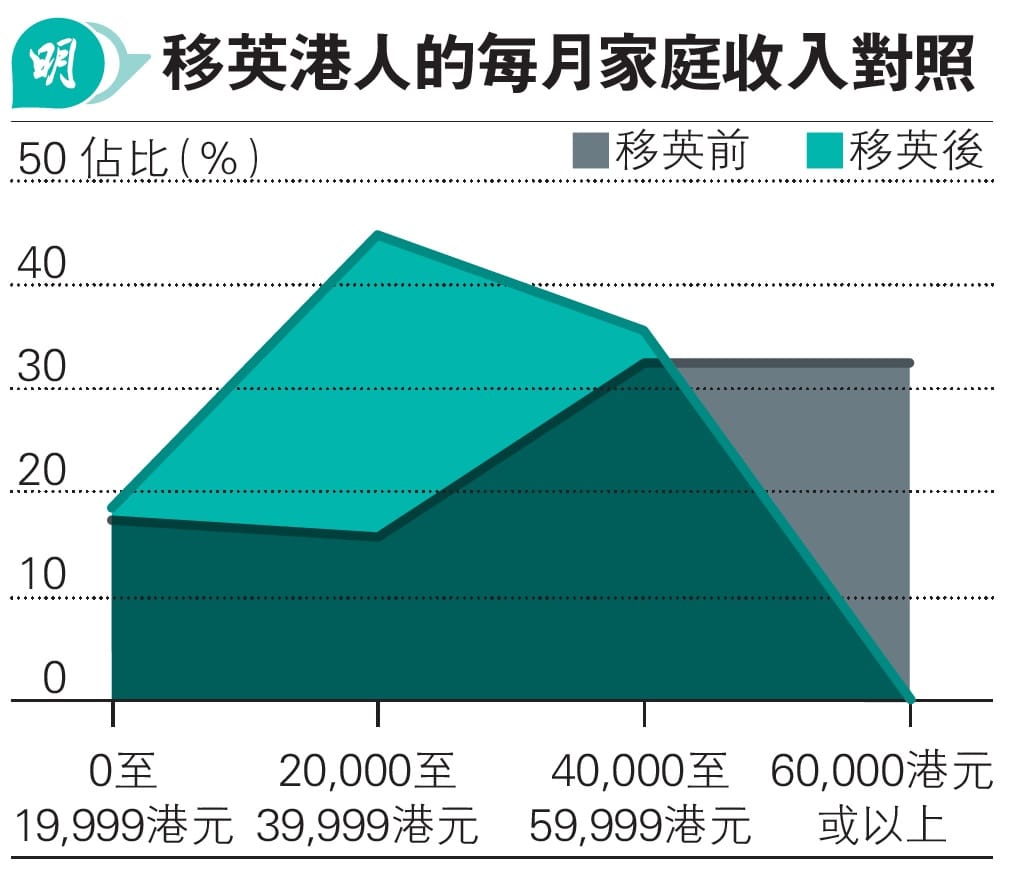

Immigration costs create economic barriers. Not surprisingly, Hong Kong residents in the UK are wealthier, more productive and have more spending power than local Hong Kong residents. Their average monthly household income before leaving Hong Kong reached HK$46,500, which is much higher than the latest Hong Kong median of HK$30,000. However, after immigration, the average monthly income of these families dropped to HK$33,300, a drop of nearly 30% (calculated on the basis of 1 pound to 10 Hong Kong dollars). The median monthly income in the UK is about HK$26,700. Although Hong Kong residents living in the UK are still considered well-off in the country and it will not be a problem to live a middle-class life, they are obviously not as wealthy as those in Hong Kong.

The attached chart divides the number of families by income group, showing that Hong Kong families are mainly high-income before immigration. After immigration, they are generally downgraded to the middle-income level. Only a small number can stay in the same income group. There are various reasons for the sharp decrease in family income, such as changes in job types and industries, and the increase in the number of people who are unemployed or choosing to retire after immigrating. Many parents also have one of them give up their job and stay at home to take care of their children. Regardless of the reason, a reduction in household income will directly affect the quality of life. For example, consumption in leisure activities, entertainment, etc. will be reduced in disguise. Considering the high taxes and prices in the UK, we can foresee that Hong Kong people living in the UK will have to work harder in life.

Occupational mismatch: white-collar workers become blue-collar workers

In addition to the decline in overall household income, the professionalism of employed people has also been significantly downgraded. Harry Ganzeboom and other scholars who have studied social mobility for many years have established the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) to quantitatively assess the professionalism of various types of work for comparison. This index uses educational requirements, social resources and economic income to form a hierarchical scale, turning different industries into an index ranging from 0 to 100 points as an analysis reference. For example, managers have a score of 65 points and labor workers have a score of 24 points.

When interpreting the results of ISEI, readers must keep in mind that there is no distinction between high and low occupations. The numerical value does not equal the contribution to society. It only reflects the professionalism of a certain type of work. What we are most concerned about is not the numerical value, but the economic structure and personal psychological impact brought about by the change.

According to the above questionnaire data, the ISEI of Hong Kong residents who immigrated to the UK was originally 41.2 in Hong Kong, but dropped to 24.2 after moving to the UK. This high and low transition represents multiple meanings. First of all, immigrants to Hong Kong have changed from mainly working in clerical or professional jobs in the past to working in labor or technical jobs. The skills required for each job are also different, and it takes a lot of personal efforts and social resources to cultivate them. Therefore, the types of jobs for Hong Kong people have suddenly changed, reflecting a serious mismatch of human resources. Secondly, each job type and industry has its own unique social identity and values. Those who change jobs must accept that they have become a monk midway, and their families also need to adjust to changes in income and living expenses. Therefore, the life and psychological adjustments brought about by job transition affect both individuals and families. These adjustment processes are difficult and may lead to family conflicts, and severe cases may be more likely to suffer from adjustment disorder.

I believe readers also know something about career downgrades in their circle of friends. Take the author as an example. A school friend who once studied for a master's degree and a doctorate together gave up completing his doctoral thesis and working as a part-time lecturer in order to immigrate to the UK. After arriving in the UK, he worked as a warehouse attendant in a local supermarket. After chatting with a hairdresser, he learned that many Originally a respectable middle-class regular customer, he became a cashier and driver after immigrating. The online media "Mung Bean"'s "Hong Kong People" series of reports also introduced how Hong Kong people became masseurs after leaving Hong Kong and going to the UK, and how they brought their own "food stand" massage tables to travel around London. On the one hand, these stories confirm the reality of the difficult life of immigrants, and on the other hand, they show the outstanding characteristics of Hong Kong people who are flexible, adaptable, and willing to step out of their comfort zone in order to survive.

Half of Hong Kong people living in the UK are hesitant to settle down

However, not all immigrants can quickly adapt to changes in life and culture, and negative emotions arise spontaneously. The most common coping strategy they use to soothe their emotions is to connect with Hong Kong people who share the same sentiments and encourage each other through interpersonal interactions. Most Hong Kong people who immigrate to the UK do not live alone, but 88% live with family or friends. They spend an average of 9.8 hours per week on Hong Kong-related online activities, such as posting articles, reading comments, sending messages to relatives and friends living in Hong Kong, etc. The content is also inseparable from current events in Hong Kong life. Some people will frequently participate in the activities of diaspora groups to find people with similar experiences; nearly a quarter of them have returned to Hong Kong more than three times.

When it comes to future plans, 53% respondents firmly believe that they will not return to Hong Kong, 24.9% are not sure whether they will return to Hong Kong, and 21.1% plans to return to Hong Kong. For the latter two, nearly half of the people hold a wait-and-see attitude, or are waiting for an opportunity to return to Hong Kong. How to "move with emotion and understand with reason" and "call" them back is believed to be the goal under the current government's "talent grabbing" policy direction. Some voices have suggested that since overseas Hong Kong people are still concerned about the developments in Hong Kong, the Overseas Economic and Trade Office may wish to have regular contact with local Hong Kong people, systematically support expatriate organizations, organize festivals, and promote hometown feelings; foreign visiting officials should also try their best to spend time with local Hong Kong people. When they meet, they feel that they are the targets of Hong Kong's solicitation and that Hong Kong's door is always open. It is believed that these methods will have a certain influence on some Hong Kong people who are deeply homesick and unable to adapt to the UK.

Most of the people coming to Britain from Hong Kong are young and in their prime. Hong Kong has lost many talents because of their departure. Data shows that their salary levels have generally declined, the work industry is also facing tremendous changes, and their original professional abilities are not valued. Why they would rather devalue themselves than fly high and fly away, we and the government should certainly reflect and review. However, seeing that many young people living in Hong Kong are still hesitant about whether to stay or leave, the society needs to do more research of this kind so that different stakeholders can understand more about the current situation, so that everyone can make the best decision.

The living conditions of overseas Hong Kong people are like drinking water and knowing whether they are warm or cold. Some people think it is worthwhile, while others think it is not suitable. As Hong Kong people, we just need to respect their decision. It is normal for someone to experience a foreign environment, rethink their life values and goals, and then decide to return to their hometown.

Reference: Ganzeboom, HBG, De Graaf, PM, & Treiman, DJ (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21(1), 1-56.

The author Pan Lehui is a postdoctoral researcher at the Hong Kong Asia-Pacific Institute of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Pan Xuezhi is the assistant director of the Shanghai-Hong Kong Development Joint Research Institute of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Source:https://news.mingpao.com/ins/%e6%96%87%e6%91%98/article/20240725/s00022/1721822818781