The identity of Hong Kong people has long lingered between "Hong Kongers" and "Chinese". Acceptance and resistance to the mainland are regarded as indicators of "the return of people's hearts" and have attracted much public attention. Whether in academia or the media, the two identities of "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese" have long been regarded as antagonistic. However, the appearance of binary opposition between the two identities actually stems from the fact that the questionnaire design of traditional polls cannot accurately reflect the dual identification of the two identities by most citizens. Democratic Thoughts conducted a public opinion telephone survey (Note) on "One Country, Two Systems" in June this year. It abandoned the traditional questionnaire design framework to dismantle the hot topic of Hong Kong people's identity, proving that dual identity is the mainstream of Hong Kong society. It also found that "Hong Kong people" and The two identities of "Chinese" are not only not opposed to each other, but are complementary to each other.

Blind spots in poll questionnaire design

Since before and after the handover, three well-known polling organizations, the University of Hong Kong and the Chinese University of Hong Kong, have carried out long-term follow-up research on identity issues. The questionnaire designs of the three polling agencies all implicitly create a binary opposition between the identities of "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese people": they classify their identities into two types: "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese people", or categorize them as "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese people". Four types ("Hong Kong people", "Chinese people in Hong Kong", "Hong Kong people in China" and "Chinese people") were given to the respondents (questionnaires from the Center for Communication and Public Opinion Research of CUHK and the Public Opinion Research Program of the University of Hong Kong). Regardless of whether you choose one of two or four, there is a binary opposition between the two identities of "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese". That is, the more people identify with the identity of "Hong Kong people", the fewer people identify with the identity of "Chinese". "identity.

In response to this blind spot, Democratic Thinking used two separate questions in its recent public opinion telephone survey to ask citizens about their level of identification with "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese people". The survey results can answer two questions that have been ignored for a long time: (1) How many citizens identify as "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese" at the same time? (2) Are the two identities of "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese" antagonistic to each other or complementary to each other?

In recent years, the HKU Institute for Civil Affairs has also realized that identities may overlap, so it has added independent questions since 2007, using a method similar to this study to test citizens' identification with various identities. However, the HKU Private Research Institute has not published an analysis on the above two issues that have been ignored for a long time.

Breaking the misunderstanding that "Hong Kong people's national identity is weak"

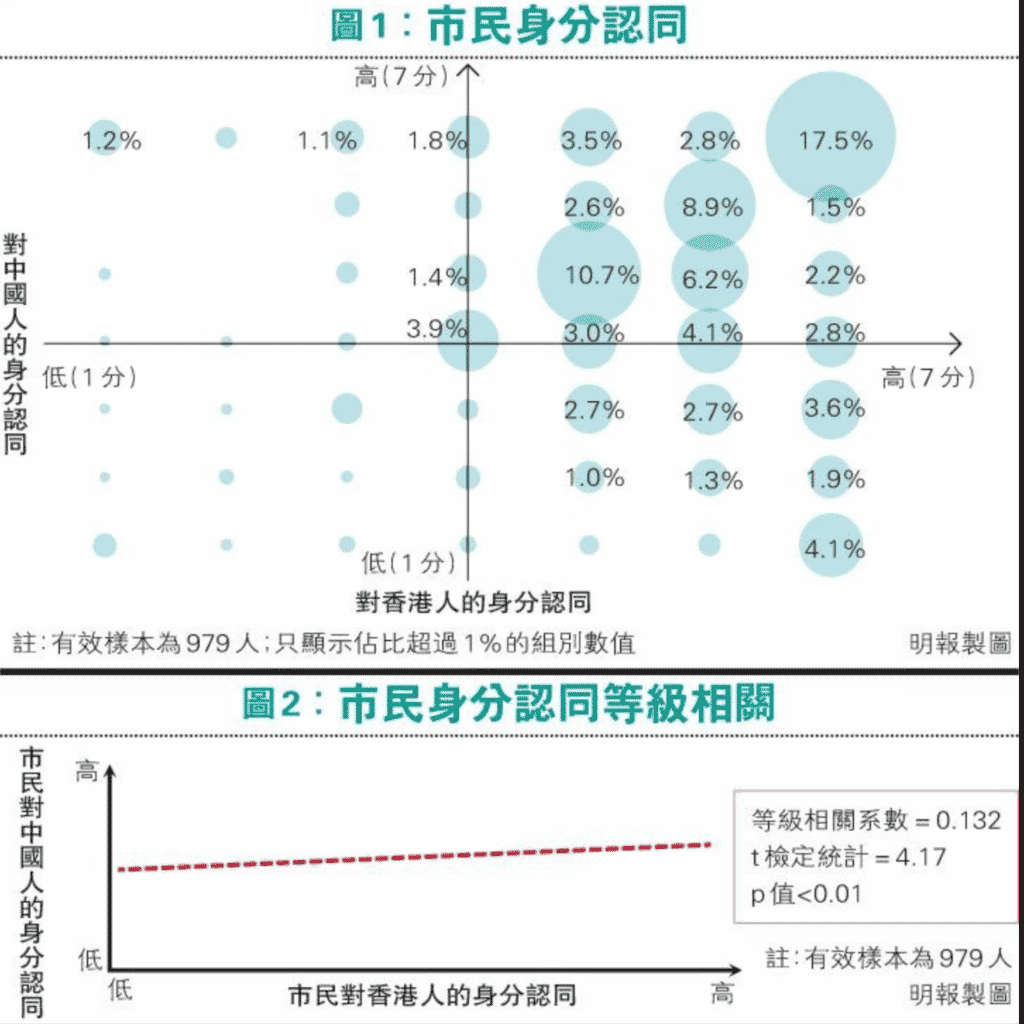

In the telephone survey, citizens' level of agreement with the two identities was measured on a scale of 1 to 7 (1 represents "strongly disagree" and 7 represents "strongly agree"). Figure 1 uses a scatter plot to display the scoring results, which are the degree of identification with "Hong Kong people" and the degree of identification with "Chinese people". 4 is the median, which represents moderate recognition and is the origin of the vertical and horizontal axes. The area on the upper right side of the coordinate axis includes 55.9% citizens who have a high level of identification with both identities (higher than 4 points), clearly showing that most citizens identify themselves as both "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese" at the same time. The dual identity breaks the misunderstanding that "Hong Kong people's national identity is weak".

Although traditional polls are better able to identify the main identities, if citizens attach equal importance to (or ignore) both identities, no matter which identity they choose, there is still a certain degree of arbitrariness. Figure 1 shows that 42.71 TP3T citizens believe that "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese people" are indistinguishable, and they will feel dilemma in making a choice under the traditional polling framework. Moreover, the three groups with the largest number of people all have strong identification with "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese people" (that is, the scores are 5 points, 6 points or 7 points), which proves that the tracking polls since the handover have been consistent It underestimated the dual recognition of a large number of citizens.

Strengthening the identity of Hong Kong people can help cultivate national identity

Are the identities of "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese" antagonistic to each other or complementary to each other? From Figure 2, it is found that the two identities show a very significant positive correlation, with a rank correlation coefficient of 0.132 and a confidence level of 99%. The results indicate that the two identities complement each other, that is, the more citizens identify as "Hong Kong people", the more they identify as "Chinese" and vice versa.

Local consciousness has been focused by society due to the intensification of cross-border conflicts. In fact, it is not opposed to national identity. The two identities contain many common elements, such as blood, geography, language and culture. It is not surprising that the two identities complement each other. The blind spot in the design of past polls was that citizens with dual identities were seriously underestimated. Traditional polls believe that only older, less educated, and pro-establishment citizens are more likely to identify as "Chinese." However, democratic thinking has found that those who consider themselves to be both "Hong Kongers" and "Chinese" cover everyone from 30 to senior citizens. Age groups, all educational levels (primary school to graduate school) and most of the political spectrum, including not only centrists and establishments, but also democrats. This study found that 55%’s democratic parties strongly identify with both “Hong Kong people” and “Chinese people”. However, among the local/self-determination faction, only 20% has a strong identification with "Chinese", while the identification of teenagers (18 to 29 years old) with "Chinese" appears to be polarized: 43% teenagers have a higher identification with "Chinese" ( Higher than 4 points), 39% teenagers have a low level of identification with "Chinese" (lower than 4 points), and the remaining 18% have a medium level of identification (4 points).

In summary, dual identity is the mainstream of Hong Kong society (the number of local/self-determination groups is small, accounting for only 6.4% of the sample). Although teenagers' identification with "Chinese" is weak, among teenagers, the number of teenagers who have a higher identification with "Chinese" is still slightly more than those with a lower identification. We do not need to be overly pessimistic about cultivating the national identity of teenagers.

The identity of "Hong Kong people" and "Chinese" complement each other. Enhancing the identity of Hong Kong people and cultivating national identity are not antagonistic. Politicians do not need to avoid talking about or deliberately belittle either of the two identities. Only by establishing a solid dual identity can we provide favorable conditions for implementing one country, two systems.

Note: For detailed report, see http://pathofdemocracy.hk/zh-hant/1c2s-index/

(Editor's note: The title of the article was proposed by the editor; the original title of the manuscript was "Looking at the "return of the people's hearts" from the blind spot of the poll - the neglected dual identity")

The author Song Enrong is a director of Democratic Ideas and a visiting professor of the Department of Economics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Pan Xuezhi is a research assistant at the Shanghai-Hong Kong Development Joint Research Institute of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.